Risky play: Unlearning our Fears

Angela Vencio

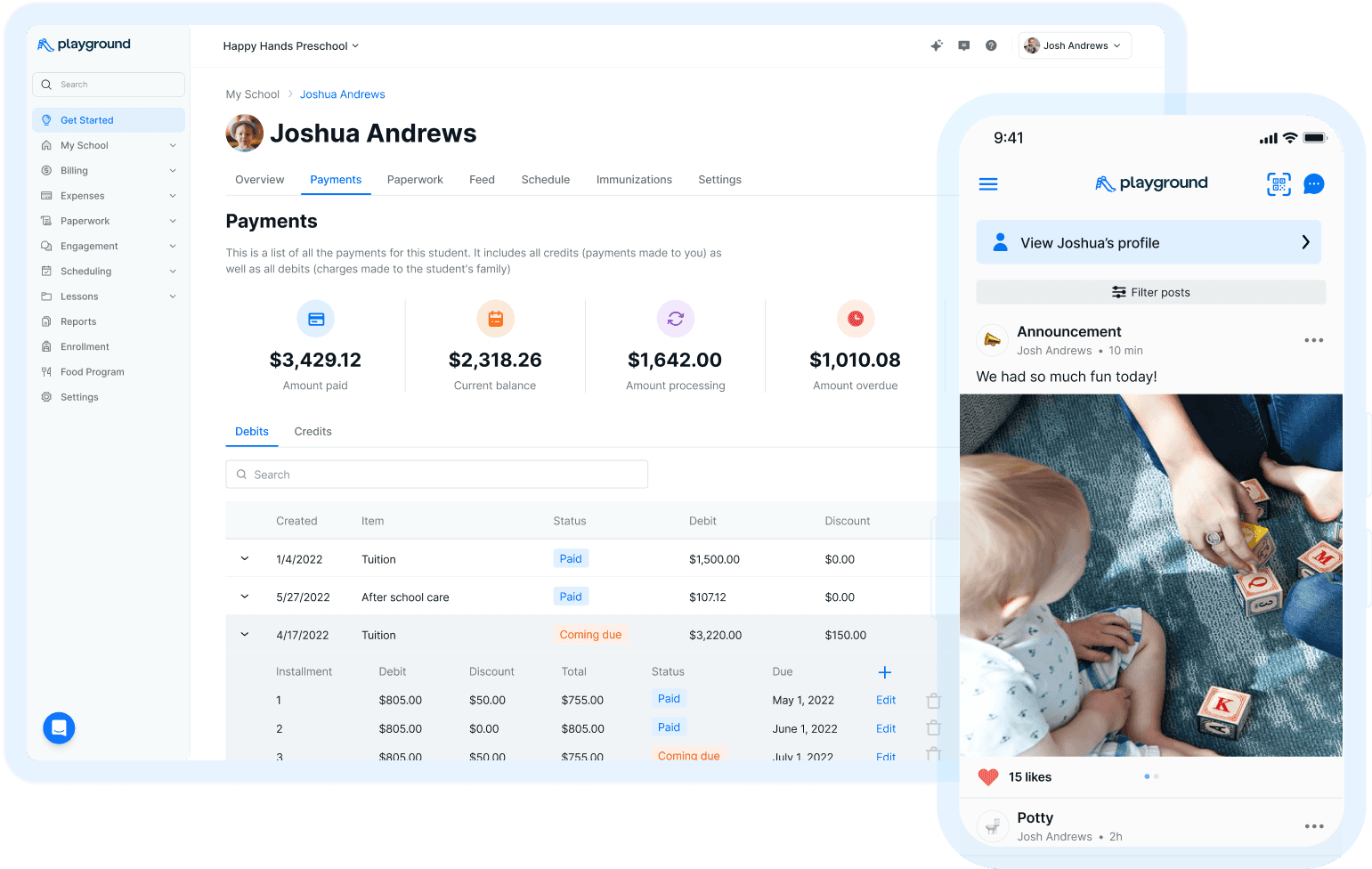

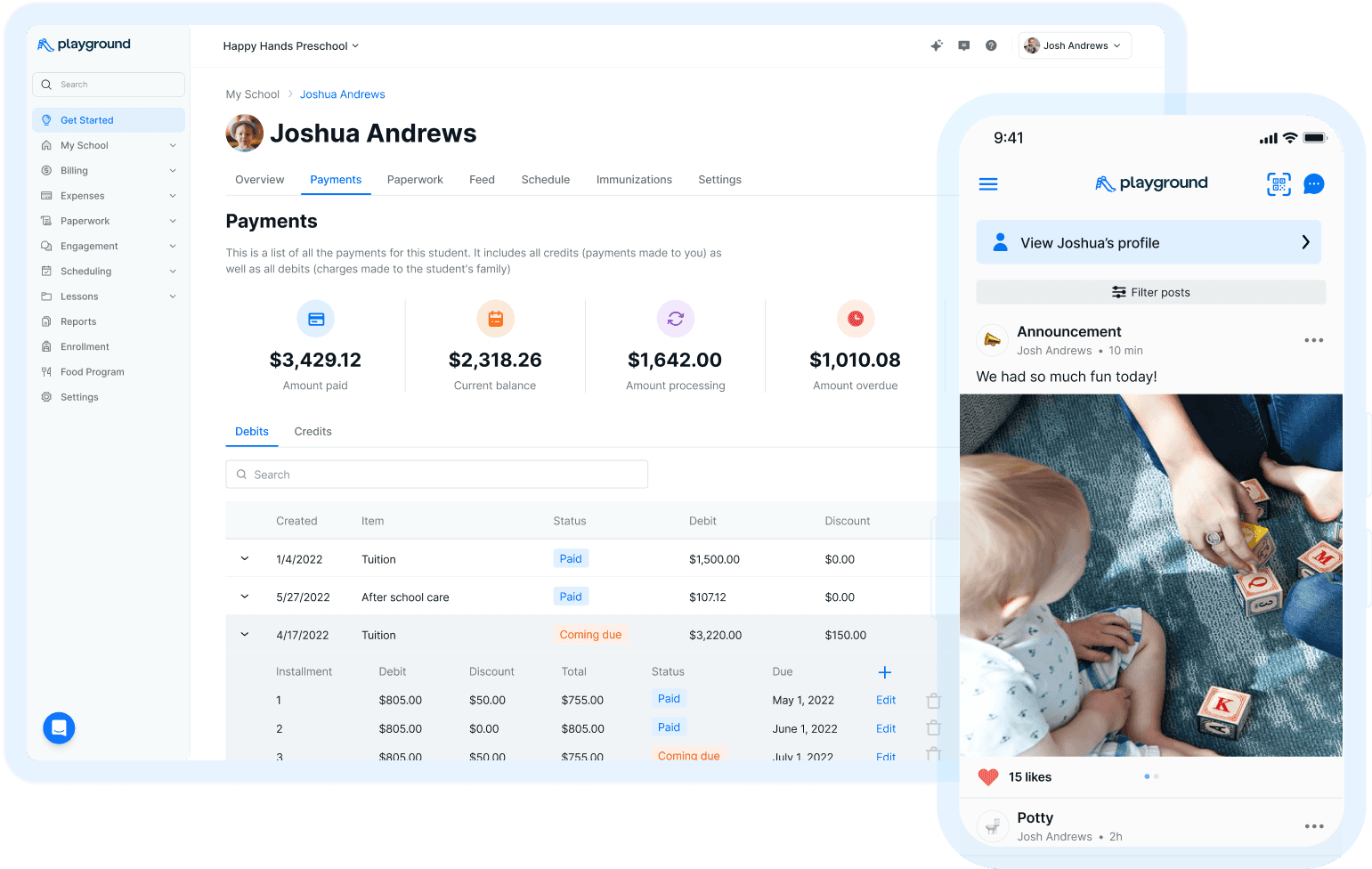

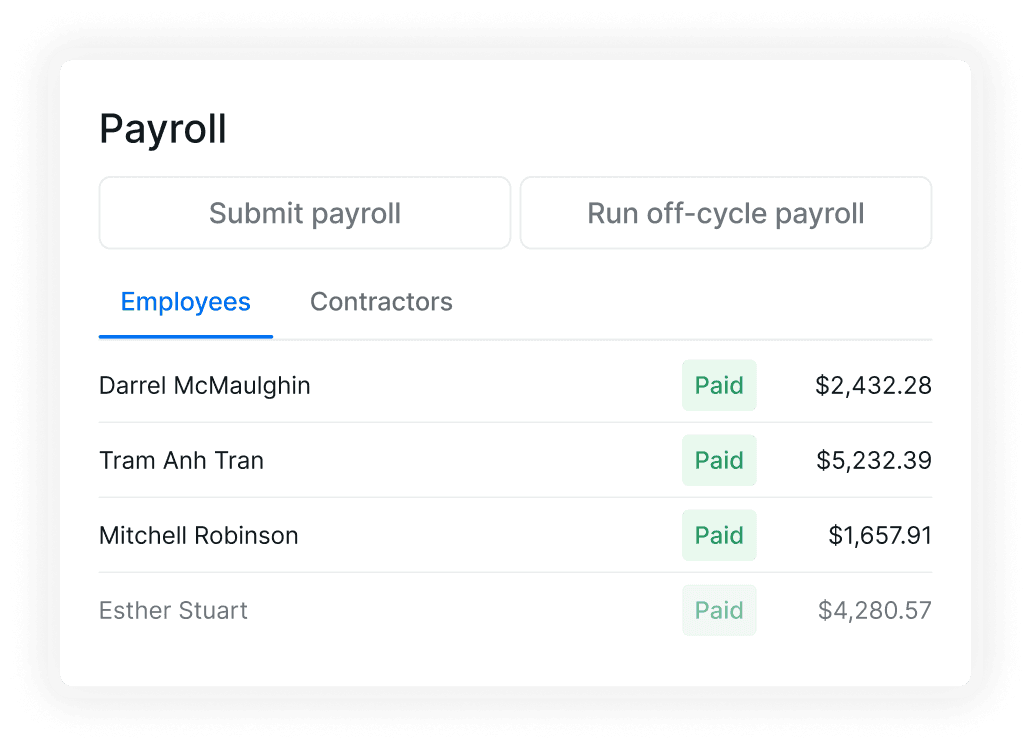

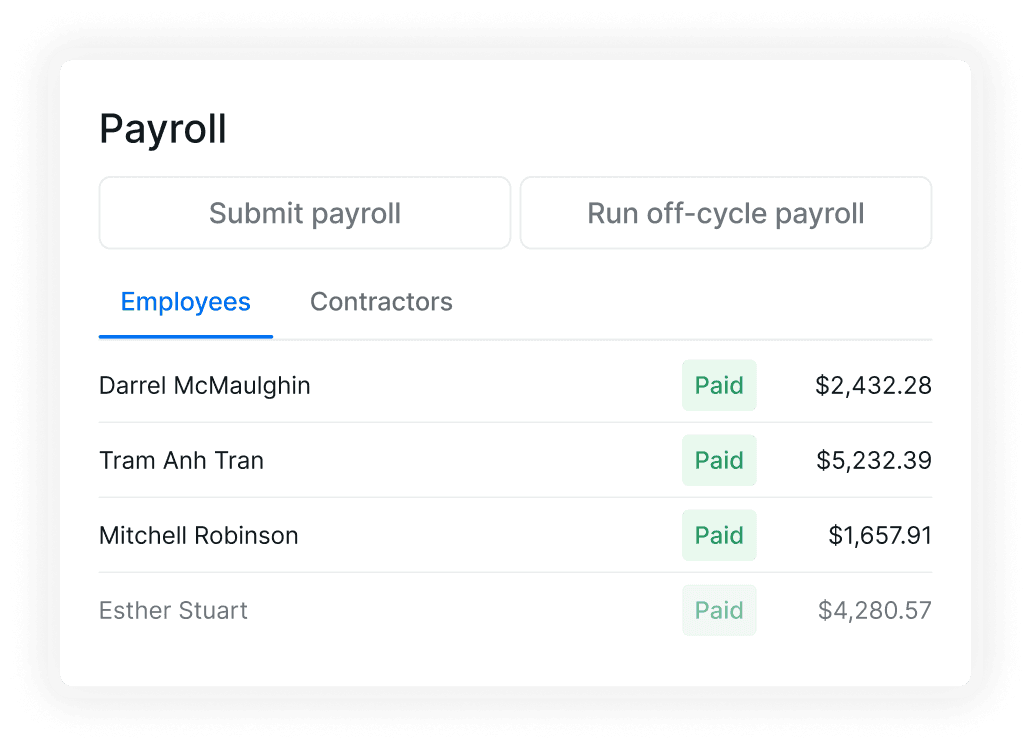

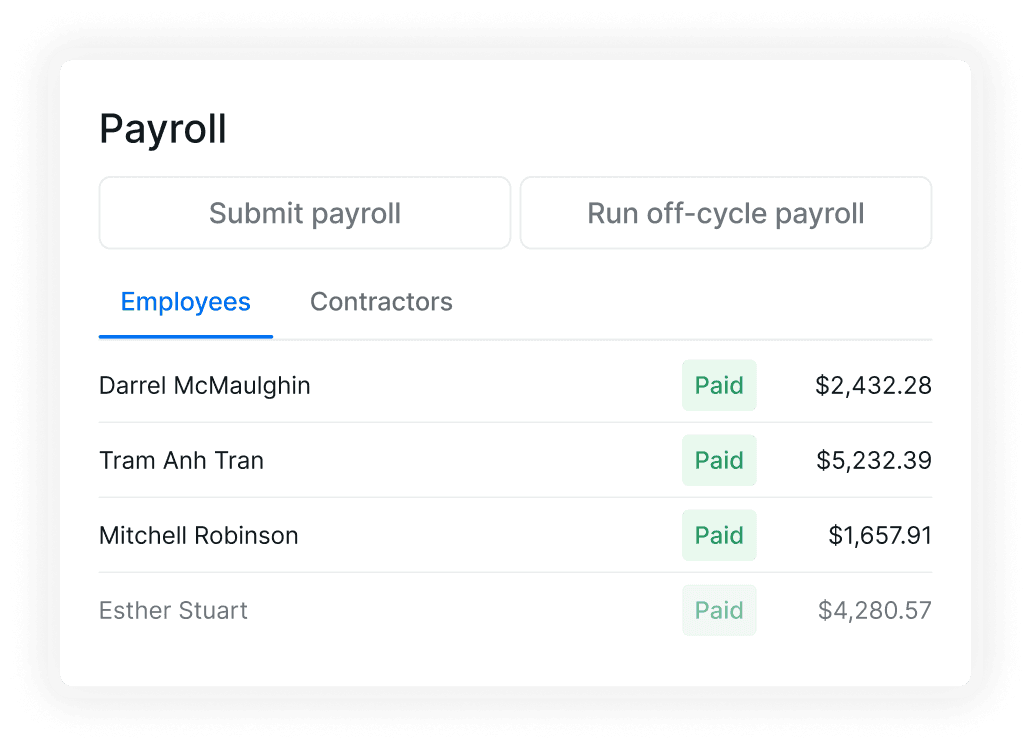

Make your families & teachers happier

All-in-one child care management platform with billing, attendance, registration, communication, payroll, and more!

5.0 Rating

Make your families & teachers happier

All-in-one child care management platform with billing, attendance, registration, communication, payroll, and more!

5.0 Rating

Risky play is defined as “thrilling and exciting forms of physical play that involve uncertainty and a risk of physical injury” (Sandseter, 2010). Risky play falls under a spectrum – it looks different to everybody! There are 6 main categories that constitute risky play, and it is okay to agree or disagree with one or more:

1. Play with great heights

2. Play with high speed

3. Play with harmful tools

4. Play near dangerous elements (ex. water, ice, fire)

5. Rough and tumble play

6. Play where the children can disappear/get lost

The Effect of COVID-19 on Risky Play

Following a pandemic where children were left to entertain themselves at home, play behaviors in children have shifted. Research has shown that the pandemic showed a decrease in physical activity, and an increase in sedentary behavior, social media use and screen time in school age children aged 8-16 years (Pfefferbaum and Van Horn, 2022), as well as a decrease in outdoor play, and longer sleep times for children aged 5 to 17 years.

Times have certainly changed - playground structures and outdoor games with friends have been replaced with TikToks and video games. Risky play opportunities have inevitably decreased – but why is this a bad thing? What are children missing out on by being deprived of opportunities for risky play?

Benefits of Risky Play

Risky play lends itself to the opportunity of building gross motor and physical growth and development skills that may not be practiced as often in an indoor setting, like running, sprinting, hopping, and climbing. It also creates an environment for positive social interactions. “Children seeing other children try new skills or play in unique ways gives them the confidence and encouragement to also try new skills” (Hilland Denver, p. 83). It helps create a bond between child and caregiver, where the child will feel more comfortable to ask for help. Finally, it gives children the chance to reflect on their own limits and build their own risk management and environment assessment skills by asking themselves: Was that too easy or too difficult for me? Was that a safe idea? How can I do that more safely?

Barriers to Risky Play

Classroom and parenting structures may inhibit risky play from being practiced. For example, there may be one parent or teacher who encourages rough and tumble play, while the other discourages it. This inconsistency can lend itself to forming anxiety about disappointing one caregiver, or an unclear expectation of whether or not they can take risks freely.

Child development theorist Jean Piaget coined the term “schema”, which he defined as “the way we see the world through a pattern of learning, linking perceptions, ideas and actions”. Children create schemas about the people around them as a way of making sense of the world. In a scenario where there is a more permissive caregiver, there is also a cautious one. This child then creates a schema for each caregiver – while they may feel comfortable exploring risky play opportunities with the permissive caregiver, their schema for the “cautious” inhibits them from feeling and acting on the same level of comfort. As parents and caregivers, how we perceive risky play sets the tone for how children perceive risky play. In a study by Oliver, Nesbi, McCloy, Harvey & Dodd (2022), some parents reported that they had difficulty encouraging outdoor play due to judgment from other parents, and more comfort playing indoors. This highlights that oftentimes, caregivers may unknowingly restrict children’s opportunities for risky play for their own convenience. Supporting caregivers to overcome this anxiety about judgment and fear of leaving their comfort zone is an important step in allowing children to freely explore.

A lack of knowledge and a fear around how risky play can be implemented safely may be the answer to why parents and caregivers are so hesitant to break free from a sheltered play style. This thought is echoed by the findings in Spencer et. al (2021)’s study, where ECEs reported that the fear of liability of caring for other people’s children as a professional outweighed their desire to allow risky play opportunities in the classroom. Thus, supporting educators to make informed decisions to allow risky play to occur in a manageable way is imperative to children’s physical growth and development.

Many questions surround the idea of risky play – how can it be implemented safely? How can caregivers overcome their trauma about risky play as children?

How to Safely Support Risky Play

Risk, Benefit, Management Analysis

Play experiences can be screened for safety using the risk, benefit, management analysis to encourage risky safe play. Consider the risk – is the child in any immediate danger? Is the play environment appropriate for the activity planned? Then, consider the benefit – how do children benefit from this play? Finally, consider the management – what is the adult’s role in the play to make this safe? Does this entail restructuring the environment? Splitting up the group? Providing clear rules and expectations to the children before the activity starts?

Set up the Play Environment

While it is important to consider licensing requirements that may restrict teachers from certain risky play experiences, remember that as qualified professionals, we have the education and knowledge to reflect on how we can modify the opportunity to meet licensing requirements. If an outdoor space is too large or the ratio of teachers is not enough to adequately supervise risky play of large groups in a large space, consider how you can instead implement the activity in a classroom, or with a small group at a time. Consider the groupings, the size of the classroom, the amount of teachers available, and how indoor space can be transformed. By considering the play environment, it allows for safe play, while still reaping the benefits of risky play.

17 Second Rule

“Brussoni advises, 17 seconds. Step back, she says, and “see how your child is reacting to the situation so that you can actually get a better sense of what they’re capable of when you’re not getting in the way.” (Toole, 2021) Being able to step back and watch without intervention allows children to manage their own risks and reflect on their own boundaries. Children should be given enough time and space to problem-solve on their own.

Child developmental theorist Lev Vygotsky coined the term “scaffolding”, which means to assist children periodically until they can master a task independently. It is a theory that can, and should, be practiced in risky play; Helping children to take risks in smaller, more manageable steps is a great confidence builder for children with a predisposed anxiety to dangerous play, as they learn to control their bodies in space with the support of their caregivers. It may also alleviate any anxiety from the caregiver, who can be reassured from this overtime that the child is capable.

Bandaids, scrapes and bruises are all a part of childhood. In a time and age where we are recovering from the lasting effects of a pandemic, it is important that we step up to give children back the childhood they were stripped of. It’s time that we unlearn our fears, so that children can face theirs.

References

Hilland, D. (2019) Risky play: Exploring perspectives of parents in Ontario [PDF]. Retrieved October 2022, from https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/75662/Hilland-Denver-MA-HPRO-April-2019.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1

Oliver, B., Nesbit, R., McCloy, R., Harvey, K. & Dodd, H. (2022) Parent perceived barriers and facilitators of children’s adventurous play in Britain: A framework analysis. BMC Public Health, 22(636), Retrieved October 2022, from https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-13019-w

Pfefferbaum, B. & Van Horn, R. (2022) Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour In Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Mental Health. Current Psychiatry Reports, 24(493-501). Retrieved from October 2022, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11920-022-01366-9#Sec5.

Sandseter, E. B. H. (2010). A qualitative study of risky play among preschool children. Retrieved October 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236986868_Scaryfunny_-_A_qualitative_study_of_risky_play_among_preschool_children.

Spencer, RA., Joshi N., Branje K., Murray N., Kirk SF., Stone MR. (2021) Early childhood educator perceptions of risky play in an outdoor loose parts intervention. AIMS Public Health, 8(2), p. 213-228. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8116185/.

Toole, B. (2021). Risky play for children: Why we should let kids go outside and then get out of the way. CBC. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/natureofthings/features/risky-play-for-children-why-we-should-let-kids-go-outside-and-then-get-out

Risky play is defined as “thrilling and exciting forms of physical play that involve uncertainty and a risk of physical injury” (Sandseter, 2010). Risky play falls under a spectrum – it looks different to everybody! There are 6 main categories that constitute risky play, and it is okay to agree or disagree with one or more:

1. Play with great heights

2. Play with high speed

3. Play with harmful tools

4. Play near dangerous elements (ex. water, ice, fire)

5. Rough and tumble play

6. Play where the children can disappear/get lost

The Effect of COVID-19 on Risky Play

Following a pandemic where children were left to entertain themselves at home, play behaviors in children have shifted. Research has shown that the pandemic showed a decrease in physical activity, and an increase in sedentary behavior, social media use and screen time in school age children aged 8-16 years (Pfefferbaum and Van Horn, 2022), as well as a decrease in outdoor play, and longer sleep times for children aged 5 to 17 years.

Times have certainly changed - playground structures and outdoor games with friends have been replaced with TikToks and video games. Risky play opportunities have inevitably decreased – but why is this a bad thing? What are children missing out on by being deprived of opportunities for risky play?

Benefits of Risky Play

Risky play lends itself to the opportunity of building gross motor and physical growth and development skills that may not be practiced as often in an indoor setting, like running, sprinting, hopping, and climbing. It also creates an environment for positive social interactions. “Children seeing other children try new skills or play in unique ways gives them the confidence and encouragement to also try new skills” (Hilland Denver, p. 83). It helps create a bond between child and caregiver, where the child will feel more comfortable to ask for help. Finally, it gives children the chance to reflect on their own limits and build their own risk management and environment assessment skills by asking themselves: Was that too easy or too difficult for me? Was that a safe idea? How can I do that more safely?

Barriers to Risky Play

Classroom and parenting structures may inhibit risky play from being practiced. For example, there may be one parent or teacher who encourages rough and tumble play, while the other discourages it. This inconsistency can lend itself to forming anxiety about disappointing one caregiver, or an unclear expectation of whether or not they can take risks freely.

Child development theorist Jean Piaget coined the term “schema”, which he defined as “the way we see the world through a pattern of learning, linking perceptions, ideas and actions”. Children create schemas about the people around them as a way of making sense of the world. In a scenario where there is a more permissive caregiver, there is also a cautious one. This child then creates a schema for each caregiver – while they may feel comfortable exploring risky play opportunities with the permissive caregiver, their schema for the “cautious” inhibits them from feeling and acting on the same level of comfort. As parents and caregivers, how we perceive risky play sets the tone for how children perceive risky play. In a study by Oliver, Nesbi, McCloy, Harvey & Dodd (2022), some parents reported that they had difficulty encouraging outdoor play due to judgment from other parents, and more comfort playing indoors. This highlights that oftentimes, caregivers may unknowingly restrict children’s opportunities for risky play for their own convenience. Supporting caregivers to overcome this anxiety about judgment and fear of leaving their comfort zone is an important step in allowing children to freely explore.

A lack of knowledge and a fear around how risky play can be implemented safely may be the answer to why parents and caregivers are so hesitant to break free from a sheltered play style. This thought is echoed by the findings in Spencer et. al (2021)’s study, where ECEs reported that the fear of liability of caring for other people’s children as a professional outweighed their desire to allow risky play opportunities in the classroom. Thus, supporting educators to make informed decisions to allow risky play to occur in a manageable way is imperative to children’s physical growth and development.

Many questions surround the idea of risky play – how can it be implemented safely? How can caregivers overcome their trauma about risky play as children?

How to Safely Support Risky Play

Risk, Benefit, Management Analysis

Play experiences can be screened for safety using the risk, benefit, management analysis to encourage risky safe play. Consider the risk – is the child in any immediate danger? Is the play environment appropriate for the activity planned? Then, consider the benefit – how do children benefit from this play? Finally, consider the management – what is the adult’s role in the play to make this safe? Does this entail restructuring the environment? Splitting up the group? Providing clear rules and expectations to the children before the activity starts?

Set up the Play Environment

While it is important to consider licensing requirements that may restrict teachers from certain risky play experiences, remember that as qualified professionals, we have the education and knowledge to reflect on how we can modify the opportunity to meet licensing requirements. If an outdoor space is too large or the ratio of teachers is not enough to adequately supervise risky play of large groups in a large space, consider how you can instead implement the activity in a classroom, or with a small group at a time. Consider the groupings, the size of the classroom, the amount of teachers available, and how indoor space can be transformed. By considering the play environment, it allows for safe play, while still reaping the benefits of risky play.

17 Second Rule

“Brussoni advises, 17 seconds. Step back, she says, and “see how your child is reacting to the situation so that you can actually get a better sense of what they’re capable of when you’re not getting in the way.” (Toole, 2021) Being able to step back and watch without intervention allows children to manage their own risks and reflect on their own boundaries. Children should be given enough time and space to problem-solve on their own.

Child developmental theorist Lev Vygotsky coined the term “scaffolding”, which means to assist children periodically until they can master a task independently. It is a theory that can, and should, be practiced in risky play; Helping children to take risks in smaller, more manageable steps is a great confidence builder for children with a predisposed anxiety to dangerous play, as they learn to control their bodies in space with the support of their caregivers. It may also alleviate any anxiety from the caregiver, who can be reassured from this overtime that the child is capable.

Bandaids, scrapes and bruises are all a part of childhood. In a time and age where we are recovering from the lasting effects of a pandemic, it is important that we step up to give children back the childhood they were stripped of. It’s time that we unlearn our fears, so that children can face theirs.

References

Hilland, D. (2019) Risky play: Exploring perspectives of parents in Ontario [PDF]. Retrieved October 2022, from https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/75662/Hilland-Denver-MA-HPRO-April-2019.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1

Oliver, B., Nesbit, R., McCloy, R., Harvey, K. & Dodd, H. (2022) Parent perceived barriers and facilitators of children’s adventurous play in Britain: A framework analysis. BMC Public Health, 22(636), Retrieved October 2022, from https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-13019-w

Pfefferbaum, B. & Van Horn, R. (2022) Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour In Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Mental Health. Current Psychiatry Reports, 24(493-501). Retrieved from October 2022, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11920-022-01366-9#Sec5.

Sandseter, E. B. H. (2010). A qualitative study of risky play among preschool children. Retrieved October 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236986868_Scaryfunny_-_A_qualitative_study_of_risky_play_among_preschool_children.

Spencer, RA., Joshi N., Branje K., Murray N., Kirk SF., Stone MR. (2021) Early childhood educator perceptions of risky play in an outdoor loose parts intervention. AIMS Public Health, 8(2), p. 213-228. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8116185/.

Toole, B. (2021). Risky play for children: Why we should let kids go outside and then get out of the way. CBC. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/natureofthings/features/risky-play-for-children-why-we-should-let-kids-go-outside-and-then-get-out

Risky play is defined as “thrilling and exciting forms of physical play that involve uncertainty and a risk of physical injury” (Sandseter, 2010). Risky play falls under a spectrum – it looks different to everybody! There are 6 main categories that constitute risky play, and it is okay to agree or disagree with one or more:

1. Play with great heights

2. Play with high speed

3. Play with harmful tools

4. Play near dangerous elements (ex. water, ice, fire)

5. Rough and tumble play

6. Play where the children can disappear/get lost

The Effect of COVID-19 on Risky Play

Following a pandemic where children were left to entertain themselves at home, play behaviors in children have shifted. Research has shown that the pandemic showed a decrease in physical activity, and an increase in sedentary behavior, social media use and screen time in school age children aged 8-16 years (Pfefferbaum and Van Horn, 2022), as well as a decrease in outdoor play, and longer sleep times for children aged 5 to 17 years.

Times have certainly changed - playground structures and outdoor games with friends have been replaced with TikToks and video games. Risky play opportunities have inevitably decreased – but why is this a bad thing? What are children missing out on by being deprived of opportunities for risky play?

Benefits of Risky Play

Risky play lends itself to the opportunity of building gross motor and physical growth and development skills that may not be practiced as often in an indoor setting, like running, sprinting, hopping, and climbing. It also creates an environment for positive social interactions. “Children seeing other children try new skills or play in unique ways gives them the confidence and encouragement to also try new skills” (Hilland Denver, p. 83). It helps create a bond between child and caregiver, where the child will feel more comfortable to ask for help. Finally, it gives children the chance to reflect on their own limits and build their own risk management and environment assessment skills by asking themselves: Was that too easy or too difficult for me? Was that a safe idea? How can I do that more safely?

Barriers to Risky Play

Classroom and parenting structures may inhibit risky play from being practiced. For example, there may be one parent or teacher who encourages rough and tumble play, while the other discourages it. This inconsistency can lend itself to forming anxiety about disappointing one caregiver, or an unclear expectation of whether or not they can take risks freely.

Child development theorist Jean Piaget coined the term “schema”, which he defined as “the way we see the world through a pattern of learning, linking perceptions, ideas and actions”. Children create schemas about the people around them as a way of making sense of the world. In a scenario where there is a more permissive caregiver, there is also a cautious one. This child then creates a schema for each caregiver – while they may feel comfortable exploring risky play opportunities with the permissive caregiver, their schema for the “cautious” inhibits them from feeling and acting on the same level of comfort. As parents and caregivers, how we perceive risky play sets the tone for how children perceive risky play. In a study by Oliver, Nesbi, McCloy, Harvey & Dodd (2022), some parents reported that they had difficulty encouraging outdoor play due to judgment from other parents, and more comfort playing indoors. This highlights that oftentimes, caregivers may unknowingly restrict children’s opportunities for risky play for their own convenience. Supporting caregivers to overcome this anxiety about judgment and fear of leaving their comfort zone is an important step in allowing children to freely explore.

A lack of knowledge and a fear around how risky play can be implemented safely may be the answer to why parents and caregivers are so hesitant to break free from a sheltered play style. This thought is echoed by the findings in Spencer et. al (2021)’s study, where ECEs reported that the fear of liability of caring for other people’s children as a professional outweighed their desire to allow risky play opportunities in the classroom. Thus, supporting educators to make informed decisions to allow risky play to occur in a manageable way is imperative to children’s physical growth and development.

Many questions surround the idea of risky play – how can it be implemented safely? How can caregivers overcome their trauma about risky play as children?

How to Safely Support Risky Play

Risk, Benefit, Management Analysis

Play experiences can be screened for safety using the risk, benefit, management analysis to encourage risky safe play. Consider the risk – is the child in any immediate danger? Is the play environment appropriate for the activity planned? Then, consider the benefit – how do children benefit from this play? Finally, consider the management – what is the adult’s role in the play to make this safe? Does this entail restructuring the environment? Splitting up the group? Providing clear rules and expectations to the children before the activity starts?

Set up the Play Environment

While it is important to consider licensing requirements that may restrict teachers from certain risky play experiences, remember that as qualified professionals, we have the education and knowledge to reflect on how we can modify the opportunity to meet licensing requirements. If an outdoor space is too large or the ratio of teachers is not enough to adequately supervise risky play of large groups in a large space, consider how you can instead implement the activity in a classroom, or with a small group at a time. Consider the groupings, the size of the classroom, the amount of teachers available, and how indoor space can be transformed. By considering the play environment, it allows for safe play, while still reaping the benefits of risky play.

17 Second Rule

“Brussoni advises, 17 seconds. Step back, she says, and “see how your child is reacting to the situation so that you can actually get a better sense of what they’re capable of when you’re not getting in the way.” (Toole, 2021) Being able to step back and watch without intervention allows children to manage their own risks and reflect on their own boundaries. Children should be given enough time and space to problem-solve on their own.

Child developmental theorist Lev Vygotsky coined the term “scaffolding”, which means to assist children periodically until they can master a task independently. It is a theory that can, and should, be practiced in risky play; Helping children to take risks in smaller, more manageable steps is a great confidence builder for children with a predisposed anxiety to dangerous play, as they learn to control their bodies in space with the support of their caregivers. It may also alleviate any anxiety from the caregiver, who can be reassured from this overtime that the child is capable.

Bandaids, scrapes and bruises are all a part of childhood. In a time and age where we are recovering from the lasting effects of a pandemic, it is important that we step up to give children back the childhood they were stripped of. It’s time that we unlearn our fears, so that children can face theirs.

References

Hilland, D. (2019) Risky play: Exploring perspectives of parents in Ontario [PDF]. Retrieved October 2022, from https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/75662/Hilland-Denver-MA-HPRO-April-2019.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1

Oliver, B., Nesbit, R., McCloy, R., Harvey, K. & Dodd, H. (2022) Parent perceived barriers and facilitators of children’s adventurous play in Britain: A framework analysis. BMC Public Health, 22(636), Retrieved October 2022, from https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-13019-w

Pfefferbaum, B. & Van Horn, R. (2022) Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour In Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Mental Health. Current Psychiatry Reports, 24(493-501). Retrieved from October 2022, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11920-022-01366-9#Sec5.

Sandseter, E. B. H. (2010). A qualitative study of risky play among preschool children. Retrieved October 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236986868_Scaryfunny_-_A_qualitative_study_of_risky_play_among_preschool_children.

Spencer, RA., Joshi N., Branje K., Murray N., Kirk SF., Stone MR. (2021) Early childhood educator perceptions of risky play in an outdoor loose parts intervention. AIMS Public Health, 8(2), p. 213-228. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8116185/.

Toole, B. (2021). Risky play for children: Why we should let kids go outside and then get out of the way. CBC. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/natureofthings/features/risky-play-for-children-why-we-should-let-kids-go-outside-and-then-get-out

Playground is the only app directors need to run their early child care center. Playground manages billing, attendance, registration, communication, paperwork, reporting, and more for child care programs. 100,000+ directors, teachers, and families trust Playground to simplify their lives.

Learn more by scheduling a free personalized demo.

See what Playground can do for you

Learn how our top-rated child care management platform can make your families & teachers happier while lowering your costs

Explore more

Stay in the loop.

Sign up for Playground updates.

Stay in the loop.

Sign up for Playground updates.

Stay in the loop.

Sign up for the updates.

© 2024 Carline Inc. All rights reserved.

© 2024 Carline Inc. All rights reserved.

© 2024 Carline Inc. All rights reserved.

Risky play: Unlearning our Fears

Published Nov 22, 2022

|